|

Spectrum Management - From the Early Years to the 1990s |

|

Page 05 of 26 Former Inspectors - How inspectors were recruited! - With a Quebec perspective |

|

In the beginning, inspectors were recruited from the pool of ship radio operators because that was where experienced radio communication operators with a background in technical knowledge could be found.

Many of our people thus came from navy ships in wartime or the merchant marine.

Some of them, including Jean Lécuyer, Honoré Gagné, Max Gallant, Philibert Fontaine and many others, came from the merchant marine where they had spent many years during the last world war (fortunately without incident).

Max Gallant for one, was a young operator on a tanker. He had seen a number of his friends torpedoed in convoys. He said that he had never been at ease there, and with good reason.

Jean Lécuyer was also a radio operator and learned his technique from the Admiralty Handbook, like many other forefathers.

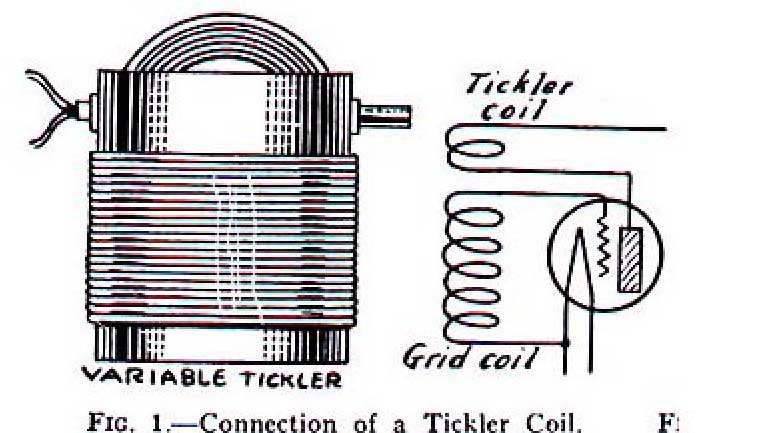

Jean recounts: "The Handbook described the ether as a propagation environment, when 30 MHz was the limit, MOPAs (master oscillator power amplifier) were new, of a 2 megawatt transmitter over 600 metres, the core of this monster being a spark gap transmitter, connected to a resonating antenna at 600 metres, ... what a glorious generator of noises..." In his early days, Marconi's "tickler-coil" (a coupled coil for adjusting regeneration) was still in use and when Jean boarded his ship, he was surprised to find a superheterodyne receiver. But it was wartime and radiation, which was very strong on the old receivers, had to be suppressed.

".... we would have been detected very rapidly considering our deck cargo of fighter planes and tanks, and some would have been quickly tempted to end our trip..."

Later on as a technician with the RCMP, Jean had to demonstrate his knowledge to superiors who believed that a transistor lasted forever!

Others came from the Armed Forces, Air or Marine Services or from the Department of Transport where they worked either as technicians or radio operators in aircraft, at land or coast stations, or on icebreakers.

Alban Violette had one of the more interesting career paths – with Group 6 in England on a British Lancaster during the last war, where he operated from Skipton on Swale, a satellite airport for Leeming. On his first mission, he used Marconi T1154 and R1155 instruments. Transferred to Leeming, the Lancasters were Canadian-made with much more sophisticated and powerful instruments from Northern Electric and Collins. After the war, he took courses at the Radio College, worked as a technician for several companies, was an instructor for the RCA AR88 and Marconi CSR5 receivers, and then became an ionospheric observer at Baker Lake.

Doing the same work in Ottawa on the Experimental Farm, he worked with Wilbur Smith, a scientist with whom he spent "many nights building a special receiver in the hope of picking up other means of communication from beyond our solar system."

Upon his return to Beaumont in Quebec, Alban was at the transmission monitoring station and then in Montreal as an inspector. Many interference investigations and anecdotes kept the day-to-day routine interesting, when those requesting service were flabbergasted by what Alban found, from rusted bolts on the antenna pylon on Mount Royal, to motor brushes on a generator at a DND radar site, to mention some of the less remarkable finds.

René Cyr has this story to tell: "... it was very difficult for new recruits to learn, since the important documents were kept in the safe and the old inspectors jealously refused to share their knowledge for fear that the new people would take their jobs. Written instructions for inspectors did not exist."

Gérard Body worked at the Lauzon Shipyard during World War II. In his free time, he entertained himself with a cousin who was interested in gadgets. He made a generator and learned Morse code from code found in a dictionary.

A radio operator course with "Father Cloutier" at the Quebec City VCC coast station followed. After an examination with inspector T.J. Moore, in 1945 he became a certified radio operator, second class, under the Department of Reconstruction and obtained his first amateur licence in 1946. He went to Moncton and Goose Bay, where he communicated with aircraft by radiotelephony and telegraph, because Department of Transport operators had replaced those of the RAF. After a few years at Dorval and Mont-Joli during construction of the DEW radar line, he was promoted to inspector in Montreal, went to the Port Alfred office and then returned to the regional office.

For many radio operators, in addition to the Admiralty Handbook, the manual by Alred A. Ghirardi entitled Modern Radio Servicing, originally published in 1935, was very well known and used by different schools and technical institutes.

At the Department of Transport, after a few years of working in Quebec, radio operators who wanted a raise or a position as a technician or inspector had to pass an examination known as "Barriers", (at the time, French was not an option! ) a session that intimidated many. They had to know their technique and their Morse code. But it was also important for candidates to receive (or not) a special mention in a so-called little black book! There were two levels of Barriers: the first involved Morse code at 20 words per minute, general technique and some practice for a raise. After two years, candidates could register for the second level, involving code at 25 words per minute, an oral technical part and a more difficult written technical part covering the maintenance of instruments in service at the Department, in addition to another part on calculating the charges for sending messages.

Many said that it was difficult in Quebec in the 1950s to land the highly coveted technician jobs. There was always the question of mastery of English, otherwise there was no hope. Was it an exclusive preserve? It was also argued that positions for bilingual inspectors were easier for Francophones to obtain.

For those who are interested, the epic story of the battle between Les Gens de l'air concerning French in aviation radio communications, and the case between politician Réal Caouette vs Air Canada, are worth reading. As for the people who monitored transmissions at the time and who heard such communications in French on the air routes in Africa and in France, and in Spanish in South America, the argument that safety was at stake because of the language was very weak.

At the national level, many had worked at monitoring stations during the war, mainly at the Ottawa station, but also out West and on the Pacific coast, on marine and aeradio stations.

At the Ottawa monitoring station, there were more than 120 operators, both men and women, with a dedicated telephone line for direct communication with a DF station in St. Hubert.

They had to be ready and listening, because submarine transmissions lasted only a few seconds, at the most a minute, and the bearings had to be taken rapidly. Submarines were even detected in the river not far from Quebec City. After the last war, most of the people went elsewhere, some to ionosphere stations in the north, others to various coast and aeronautical stations in the country, and many completed their careers at the main office in Ottawa.

In the late 1950s, there were four district offices in Quebec. The Montreal office was combined with the regional office, where the superintendent was Harry Fisher. Mr. J.L. Messier was responsible for the Quebec City office, Omer Roy for Sherbrooke and Austin Francis ran Port Alfred.

In the late 1960s, recruiting was done at the technical schools and CEGEPs.

|

|

Spectrum Management - From the Early Years to the 1990s |

Philibert

Fontaine

Philibert

Fontaine