|

But where did all the operators come

from?

In his book A Man Called Intrepid, William Stephenson recounts

the activities of Canadian William Stephenson during World War II (Camp X etc.), where operators work at various interception

stations:

"Stephenson, who had never forgotten his schoolboy exchanges

with the Morse operators on Great Lakes freighters, regarded seagoing

radiomen as among the world's best. They were accustomed to discomfort and

to working in close quarters alone. They could hang onto the faint signals

of a moving station surrounded by the clutter of other transmissions

drifting across the wave bands. At sea, they had to recognize quickly the

'fist' of the particular operator they might seek, detecting subtle

characteristics in the way he worked his key that amounted to an

individual signature." (A Man Called

Intrepid, 1976, by William Stevenson, Harcourt Brace

Jovanovich, chapter 7, pp. 50-51)

This is where many, if not the majority of operators and inspectors who

monitored and then managed the frequency spectrum, came from for many

years.

The Ottawa monitoring station during

the last war

Lloyd Cope recounts:

"In the spring of 1941, Ed Davey, Charley Rose and Gerry Gard were

responsible for the frequency standard and VAA, the master station for

the Branch's network, and also for a few intercepts at the old site near

the barn on the Experimental Farm. We were quite surprised to follow

very interesting communications about the battle to sink the Bismark, a

German ship.

During this time, Wilbur Smith, the chief standards engineer at

Transport and his boss J.W. Bain worked actively on the plans they had

proposed in conjunction with the people from the Royal Canadian Navy to

build a new station half a mile away on Merivale Road. The station began

operating in the fall of 1941 and from then until January 1942, new

operators continued to arrive to help with the interception

work.

During the same period, I and several other operators from Ottawa

were trained in direction finding at the Department's direction finding

station at St. Hubert on Montreal's south shore. This DF station had

originally been set up by the Department of Transport to provide air

control for aircraft en route over the ocean to Europe.

The Ottawa station was equipped with National HRO receivers,

Belini-Tosi style direction- finding equipment and each operating

position had its own intercom. Two technicians, René Arial and Dan

Maclean ensured that the equipment operated properly.

Around 1942, another room was added to the station that was large

enough to accommodate all the shifts, or 125 operators (both

male and female). One end of the building contained the teletype

linked directly to the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) and the operator of

this equipment alternated with the operator of the DF equipment. A

position was also reserved for listening to announcements from Berlin,

where the names of Canadians who had been taken as prisoners of war in

Germany were copied down. We passed the information on to the RCN on

16-inch records. Later on, we did the same thing with the bulletins

issued by Tokyo, but the transmissions were of very poor

quality.

There was also a position for listening to Canadian transmissions

to monitor the "bad guys" (to ensure there were no

security breaches in Canadian communications). We intercepted a

transmission on that station that we thought was clandestine, but in the

end it turned out to be a network of seminarians located close to the

Beechwood Cemetery in east Ottawa.

The VAA station occupied a small room at the monitoring station in

Ottawa. Near the end of the war, this position was in the teletype room

with the one reserved for recording the names of Canadians who had been

taken prisoner and the one for monitoring domestic stations.

Each operator used one HRO receiver. Most of the time, no specific

task was assigned, with each person looking for messages from surfaced

submarines on any frequency. With a group of 25 operators (per shift), it did not take long before this constant

sweep through the bands revealed a few frequencies being used by a

number of submarines. Three of the frequencies referenced the call signs

RXU (French station in Pétain), MMA and KYU (Bismark).

A key aspect of this interception work was that the Germans were

very methodical in everything they did. If they had used a frequency

once, they would use it again for subsequent transmissions. The

transmitters used had a very musical-like sound, which helped to

identify them on the band. Sometimes, particular operators could even be

identified by their "fist" title (by the way they handled

the key and transmitted the Morse code characters).

Because each submarine had to surface to transmit its message, the

transmissions were very short and usually resembled something like "WW

ABCD EFGH. HI". In just a few seconds, the message was copied down,

while someone called out the frequency to the RD operator. Believe it or

not, good bearings were frequent and the information was immediately

forwarded by teletype to the RCN and then to the Royal Navy that

co-ordinated all the bearings from around the Atlantic. Near the end of

the war, bearings were obtained using a cathode ray tube

display.

I remember a particular intercept around 1943. One of the

operators, Ross Stephens, almost fell off his chair when he received a

very powerful signal that could be clearly heard in the room. He

notified the DF operator and the reading showed a line to the east of

Ottawa. From subsequent information, we realized that the submarine was

in the St. Lawrence River near Quebec City.

Several times during the winter months, we were surprised to

receive transmissions from western Europe, the Baltic Sea, and so forth,

to learn that they were due to an abnormal propagation effect call the

"long skip". (The skip is the distance between

propagation hops between the sky and the earth. A long skip occurs when

the ionized layer is very high.)

The intercepts were primarily in the 6 and 7 megahertz bands, and

the ones from the stations on the Baltic Sea and the North Sea were in

the 3 megahertz band. Most of the submarine transmissions were

intercepted in the evening.

A curious event was recorded one evening when an operator

intercepted a message from a hospital ship on the coast of Africa. He

remembered intercepting a message the previous evening from the same

station with the same "fist" transmitting a message similar to the

submarine messages. The Navy was informed about it.

Around 1944, a red telephone was installed at the shift

supervisor's desk. This telephone was connected directly to Prime

Minister Mackenzie King's residence to notify him immediately of the

invasion of Africa, and then of the landing in Europe. The message was

to be sent by the BBC once all transmissions had been shut down as

agreed earlier. The transmissions grew quiet and we all held our breath

as we waited (June 6, 1944). The

announcer broadcast the two invasions. I was on duty when the news came

in, around 2 a.m., and I woke the Prime Minister to tell him. He merely

said thank you!

The 125 operators received a monthly bonus of $20 from the Navy; I

suppose it was to make up for keeping quiet and putting up with the

question "Why aren't you in uniform?"

During those years, the Army also operated a monitoring station at

Leitrim and the Navy was installed not far from the Department of

Transport station at the Experimental Farm. The Navy's station was used

for interception and their own communications. Furter, some operators

could also be assigned to specific tasks.Bill Ryan said that when he

arrived in Ottawa, his job was to monitor transmissions from the French

station at Vichy (RXU), which he had already been

doing at the Forrest Centre.

In John Bryden's book, "Best-Kept Secret, Canadian Secret

Intelligence in the Second World War", Lester Publishing, a revealing

text:

"Everything

depended on the quality of equipment, the personnel and speed. U-boat

messages were notoriously brief - as little as twenty-two seconds. An

operator might spend hours hunched over his radio set, his head clamped

in padded earphones, ears numbed by an incessant hiss. Then suddenly the

static would leap to life in staccato of Morse code. The man's hand

would slam onto a buzzer and an assistant would jump to the teletype

machine, banging the frequency numbers out on the keys. Within a couple

of seconds, the person in Bermuda would begin his (D.F.)

search." "Everything

depended on the quality of equipment, the personnel and speed. U-boat

messages were notoriously brief - as little as twenty-two seconds. An

operator might spend hours hunched over his radio set, his head clamped

in padded earphones, ears numbed by an incessant hiss. Then suddenly the

static would leap to life in staccato of Morse code. The man's hand

would slam onto a buzzer and an assistant would jump to the teletype

machine, banging the frequency numbers out on the keys. Within a couple

of seconds, the person in Bermuda would begin his (D.F.)

search."

Ernie Brown was responsible for monitoring a relatively busy

frequency, which made his work more interesting.

Ernie recounts:

"The operators were all monitoring the German coast stations and

the other stations in occupied Europe. They copied all the messages in

Morse code.

When a signal with a different modulation was sent and a manual

transmission was heard, it could only mean a mobile station or a

submarine, or a "raider" (a German warship). The message was always very

short, often in a single coded group of five letters. You had to be

quick to notify the DF operator who had to memorize the frequencies,

tune to the proper one and take the reading. He often had time for no

more than one adjustment.

I was lucky to have been assigned to monitor a very busy station,

because the work was very boring otherwise."

Around 1943, some operators monitored German transmissions, while

others monitored the Italian ones. When the war ended in Europe, it was no

longer necessary to monitor submarine transmissions. Some of the operators

had been trained in "Katakana" code (76 characters)

and were transferred to Vancouver on October 23, 1943, to monitor the

Japanese transmissions."

Still at the farm house, HRO receivers were everywhere, in the living

room, in the dining room, in the hallways and bedrooms, and operators

everywhere... The staff moved to the new station on Merivale Road in 1942.

(Del Hansen)

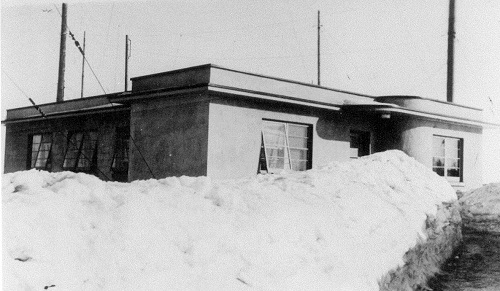

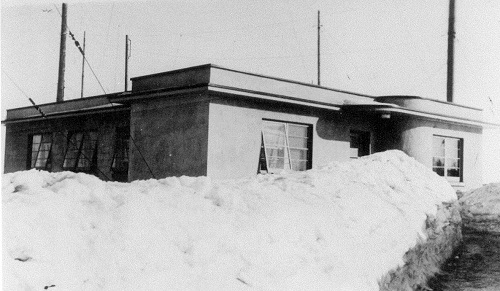

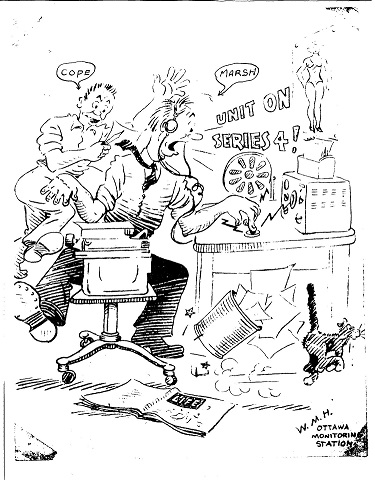

The Ottawa

monitoring station in 1942.

|

"Everything

depended on the quality of equipment, the personnel and speed. U-boat

messages were notoriously brief - as little as twenty-two seconds. An

operator might spend hours hunched over his radio set, his head clamped

in padded earphones, ears numbed by an incessant hiss. Then suddenly the

static would leap to life in staccato of Morse code. The man's hand

would slam onto a buzzer and an assistant would jump to the teletype

machine, banging the frequency numbers out on the keys. Within a couple

of seconds, the person in Bermuda would begin his (D.F.)

search."

"Everything

depended on the quality of equipment, the personnel and speed. U-boat

messages were notoriously brief - as little as twenty-two seconds. An

operator might spend hours hunched over his radio set, his head clamped

in padded earphones, ears numbed by an incessant hiss. Then suddenly the

static would leap to life in staccato of Morse code. The man's hand

would slam onto a buzzer and an assistant would jump to the teletype

machine, banging the frequency numbers out on the keys. Within a couple

of seconds, the person in Bermuda would begin his (D.F.)

search."