|

TATLOCK EARLY HISTORY by John Tatlock submitted through Laval Desbiens

Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 John Tatlock's Alumni page

CHAPTER 1

In Winnipeg, 1940 - I had enlisted in the Reserve Army Signal Corps with military training in the evenings. This was the start of my lifetime interest in radio and telecommunications. Canada had been the first country in the British Commonwealth to form a specialized Army Signal Unit when the Canadian troops served in the Boer War. Soon it was obvious that to get any higher rank in the military I would have to take a course in radio telegraphy.

Enrolling in a private school at the Russell Institute in Winnipeg with specialized classes to graduate as a Commercial Radio Operator I completed the course in record time. I then passed the Government Radio Licensing department’s exam (in 1941) to get the required Certificate of Proficiency in Radio. This qualified me to serve as the Radio Officer on all ocean vessels in the International Maritime Service.

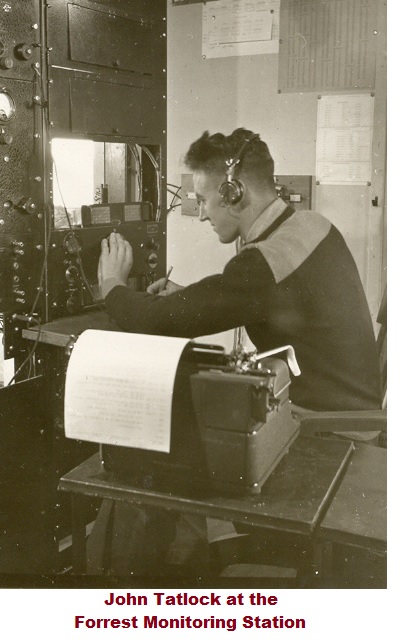

As it later turned out this was one of the best moves I had ever made. About a year later my radio operating training resulted in my being selected by the government to serve in the war in a secret Special Services unit for the Canadian Navy. This assignment required monitoring covert radio transmissions from German (and later Japanese) submarines and other enemy war ships during the remainder of the war. The ability to copy at high speed the radio transmissions of these clandestine stations led to this opportunity – to do my part in World War II service.

The above portion of my memoirs forms the foundation for writing the following chapters describing a lifetime professional career which developed in a manner far from the normal practice of an average person - taking that road less traveled.

1.1 Prelude - The Start of my Wartime Service

When I was nearing 20, I sent in my application to join the Royal Air Force which had set up a Training Unit at the RCAF headquarters at a barracks just west of the city of Winnipeg. Weeks went by with no reply, but one morning a letter came in the mail telling me to report for a medical at noon that very day. The letter had been sent back with insufficient postage and had arrived several days late. In spite of this I jumped on my bicycle (we did not own a car) and started to peddle as fast as I could the fifteen miles to the Air Force barracks located to the west of the city of Winnipeg, arriving several hours late for the appointment.

It was a bad start. I was immediately reprimanded for being late! Determined to defend myself, I declared it was not my fault and held up the double postmarked letter, returned to sender. That put the Desk Officer (from England) on the defensive and the Commanding Officer was brought in to mediate the situation with a typical English apology. I was given the military medical examination and later I leisurely rode my bicycle back home hoping that my application would be successful.

Unfortunately for me, the Royal Air Force was not as hard up at that time (1936) as they were a few years later with the start of the war. I was disqualified because I had to wear glasses. On second thought maybe this was fortunate considering what happened to some of these pilots.

As an adventurous young man, I did not think so at that time. I wanted to be a pilot. For awhile I decided to continue with the Army Signal Corps to become a radio operator.

It was at this time that I started the radio training course in the evening at the Russell Institute in Winnipeg, learning to copy the Morse Code at high speed in three months and complete the technical courses to qualify for the Commercial Radio Operators license. This permitted me to apply for a licensed radio operator career in the Merchant Marine on ships carrying armaments overseas, or alternately in the Ferry Command which was ferrying bombers across the Atlantic Ocean (this was my preference). The former would have been less interesting while the latter would have satisfied my ambition to be flying, even if not as a pilot.

Perhaps my angel was still looking after me because several months went by without a reply from either of these rather perilous war-time services.

Meanwhile, to do my part, I went to work in the military armaments factory in Transcona (south east of Winnipeg) where they were producing the high explosive Cordite. I worked the night shift, from midnight to 8 am. My job was to walk the many halls of this large plant and check the rooms to ensure that the relative humidity within any individual room in this immense factory never became lower than 98%. I had to keep hundreds of humidifiers spraying a fine mist full time to avoid any kind of a spark which would have blown us all up to “you know where”.

All the workers were required to change into special clothing and rubber boots when they entered the operational part of the building. It was an eerie place No fooling around here! All building areas were meticulously electrically grounded to discharge static electricity. In consolation, I realize this work was a lot less hazardous than being in the Merchant Marine where ships in the Atlantic were being torpedoed by the German U-Boats.

About six months later my efforts to attain certification in Proficiency in Radio Operating paid off. I received a military order to report to the special Naval Services radio corps working on a highly classified task monitoring the covert radio transmissions of the German submarine fleet. This was part of a world wide Allied network of radio stations equipped with specialized equipment designed for listening to the broadcasts of these submarines and detecting their location by triangulation of their transmitted radio signals.

This operation was headed up by the legendary Britisher “A Man called Intrepid” Sir William Stephenson who was born in Winnipeg, Jan. 11, 1896.

We reported directly to Admiralty London by overseas cable teletype. Their international headquarters was located about 60 miles outside of London in a place called Bletchley Park, which became famous for its success in deciphering the German Enigma code used by their warships.

We also monitored the transmissions of clandestine radio stations along the Atlantic shoreline which broadcast weather reports, as well as the transmissions from the captured French naval vessels, often in plain language messages (which encouraged me to learn French). These intercepted messages aided the British by reporting information on enemy naval troop movements.

The English movie film Enigma (mid 2002) gave a detailed interpretation of the activity performed by this organization of radio signal intercept stations (of which we were part). The 1979 newspaper article in the Annex to this Memoir describes the amazing activities of “Intrepid’s” war time career.

In order to transmit and send their messages to their headquarters the German submarines were required to come to the surface to expose their antennas, placing them in danger of being detected. For this reason they stayed on the air usually only about 15 seconds. At our radio monitoring post the U-boat detection action started with hearing a wailing sound during tune up of the sub’s transmitter. This was followed by transmission of a series of 10 to 15 four letter code words. It was very short (about 40 seconds) but an alert radio operator could rapidly adjust the goniometer instrument connected to the antenna circuit of his short-wave radio receiver. This rotated the receiving antenna to maximum signal.

We located and recorded the geographical bearing of the source of the signal, while other operators copied the code groups.

These reports and those identical signals heard at the other listening post locations around the world were sent to Admiralty London and Bletchley Park where mappers plotted by triangulation the submarine’s location.

This enabled the Air Force of the Allies with their aircraft and destroyers to attack the marauding enemy subs.

Early in the war the British had broken the German code and were able to decipher the content of these messages and plan their defense strategy.

My assignment in 1940 started with a months training at the radio station in Forrest Manitoba, followed by a transfer to the Ottawa Command where I was stationed for the next few years. I went on leave back home to get married in Sept.1942. Earlier that year my mother had became seriously ill and died. I had traveled home to be at her bedside – for me, a very sad memory. This is a time in one’s life when every son wishes he had done more to make his mother’s life happier.

In 1943 I was transferred to the monitoring station located just west of the Winnipeg Airport where we monitored the radio transmissions of both German and Japanese wartime naval activity. This required learning to copy the Japanese version of the Morse code which was quite different from the international code. With the surrender of the German army on May 8, 1945 we concentrated our monitoring on the activity of the Japanese fleet in the Pacific.

1.2 Next four years – Engineering Course at University of Manitoba

It was in this latter part of my wartime radio operator activity that I decided to complete my schooling and enter Engineering at the University of Manitoba. I always had a yearning to go to University so I went to evenings classes to complete Grade 12 to satisfy the University entry requirements. Next I had to convince the Dean of Engineering that what I planned to do was feasible. This was successful.

In the fall of 1943 while still working the night shift in the Government radio station I started University attending classes during the day. This continued through four long years of the rigorous Electrical Engineering course. It was difficult but eventually successful, graduating in 1947, ready to start a new career.

During the University years, my routine had been to work the night shift at the radio station from midnight to 8 am and then race across town (in those days I had a 1935 Dodge coupe with rumble seat!) to get to the morning classes at the University. This required endurance and discipline throughout the nine months of study. I never missed a class and sat in the front row to absorb every word of the lectures. At the end of the afternoon classes it was home to sleep until time to start out to get to work again before midnight.

After completion of exams at the end of each University session I was so exhausted that I vowed to quit and not return to this torture. However after the three month summer break my energy was replenished and I chose to return to the vigorous routine. Fortunately I had the co-operation of my wife to encourage me.

Mixing studying with working was difficult, however at the end of each year the feeling of accomplishment on completing the term examinations in the top quartile of the class was rewarding.

At the end of the third year I remember that I consulted with a doctor for a heart burn problem. He handed me a postcard depicting a candle in a horizontal position, burning at both ends - and a prescription for an anti-acid.

My summation of that period: The greatest moment in my entire life was when I turned in the last examination paper and feeling successful walked out of the building - to lay outstretched on the University lawn in complete relaxation in the summer sun. I will never forget it!

My proudest moment was walking at the head of the May 1947 Engineering Faculty graduation parade - which signified attaining the almost unachievable milestone. This became the start of my professional career, the recollections of which I will share in the subsequent chapters of these memoirs. Oh Happy Day!

I am fifth from the front. Bruce Webster (my lab-mate) is to my left

To be continued in Chapter 2

Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 John Tatlock's Alumni page

|

It

was later reported in the American media that during 1942 and 1943 the

German subs had sunk more than 400 Allied ships along the Atlantic

coast, many just outside of New York harbor. Save for my “guardian

angel” I could have been on one of them as radio operator.

Fortunately our enemy monitoring efforts contributed to keeping this

devastation to a minimum. The English movie named ENIGMA playing in

movie theaters around the world during 2002 was an excellent

description of the part we performed in this wartime support.

It

was later reported in the American media that during 1942 and 1943 the

German subs had sunk more than 400 Allied ships along the Atlantic

coast, many just outside of New York harbor. Save for my “guardian

angel” I could have been on one of them as radio operator.

Fortunately our enemy monitoring efforts contributed to keeping this

devastation to a minimum. The English movie named ENIGMA playing in

movie theaters around the world during 2002 was an excellent

description of the part we performed in this wartime support.