|

1984 Remember When We Had Private Receiving Station Licences? Bill Wilson VE3NR (c) The Canadian Amateur magazine Radio Amateurs of Canada Inc. CARF Publications Reprinted with permission

An early Radio Inspector's vehicle with one of the first loop antennas and inside (unseen) a specially mounted battery type all-wave receiver. Vehicles like this, modernized as the years passed, were used to locate interference sourcesnot radio receivers. (The tower in the background is not part of the mobile antenna!) Photo- Information Services, Dept. of Communications.

Thirty years ago last March 31st, Canadians heaved a great sigh of relief. The Government dropped the requirement to have a radio licence to receive broadcasting. But, 30 years ago it never envisaged today's problems created by the direct reception of broadcast programs from satellites.

The happiest group in Canada then must have been the Radio Inspectors of the Department of Transport who, for several months each year, had to fan out across the country to catch and prosecute those who did not have licences.

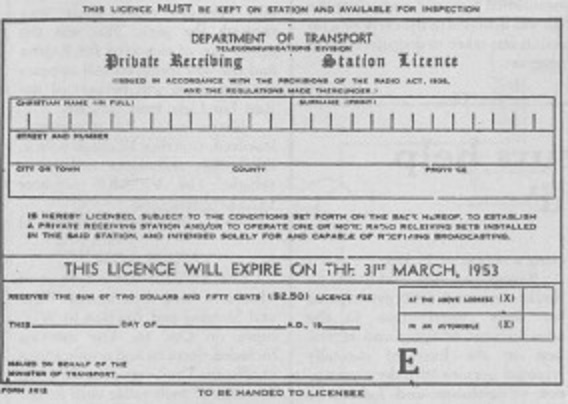

A licence was required for each broadcast receiving set. Thus, if there were two sets in the house, two licences were required. One was also needed for the car if there was a broadcast receiver in it.

All dealers who sold broadcast receivers were required by law to send the names and addresses of all purchasers to the Broadcast Receiving Licence Office in Ottawa. Licences could be bought from any radio dealer or Post Office as they sold them voluntarily as a service to the public. Each Department Radio Field Office also sold licences. Additionally, vendors were allotted areas in large towns and cities and they hired door-to-door canvassers or canvassed themselves. Books of licences were sold by the Field Offices and both dealers and vendors were required to return all books to the Inspector with the file copies showing the purchasers' names and addresses and the unsold licences, if any. The Post Offices got their books from the Head Office of the Post Office in Ottawa and sent their returns directly there.

Each licence cost $2.50 if the set was AC powered and $2.00 if it ran from batteries. Dealers and vendors got a commission of 25˘ and 15˘ per licence!

Each Friday before the banks closed, each Field Office had to make up a deposit to a special account in its local bank and make a sales report to the District Office. This represented quite a task for the Field Offices, chasing after tardy vendors, checking their books and file copies, verifying licence numbers, etc. The numbers were immense, running into the thousands per week for most Offices. Then too, the Auditors would visit the Offices unannounced to check the books. Fraud was always a problem. Some Vendor would often try to sell some copies and pocket the money. Occasionally an Inspector would find a way to take some advantage of the system. There was, more often than not, someone in the slammer somewhere for having defrauded the Government on licence fees.

All the returns eventually found their way back to the Licence Office in Ottawa where there was a large staff who analyzed and sorted things out. Data processing equipment was not used until the last years of the activity. To help the Inspectors when they made their rounds, the Ottawa office produced lists of licence holders by the Inspectors' districts. Beginning each July and lasting well into each fall, each would take his lists for an area and check each house on every street. If he found a house that was not on his list, he would make a call and ask to see the Broadcast Receiving Licence. Each Inspector developed his own method of working. The trick was to talk the occupant into allowing him to see the radio and be sure that it was working. Once he did that, it was game over for the occupant. His name would find its way through the District Office to the Licence Office where it would be checked again for a licence. If it was confirmed that the occupant did not have a licence when the Inspector called, authority would be sought and obtained from the Minister for his prosecution in court.

Inspectors looking for unlicensed receiving stations had an awfully difficult time, especially in small towns and villages where they suffered all kinds of abuse. Sometimes the RCMP had to be asked for assistance. Each Inspector had a car which was usually fitted with radio receivers to locate sources of interference. When the Department of Transport decided to equip them with loop antennas to further help locate interference sources, the public thought they were used to locate unlicensed receivers! So, when an Inspector showed up in a small town, he was instantly identified. The warning was flashed around, doors were locked, radios hidden, dogs unleashed and chewing tobacco 'chawed up' to the ready. Much to the annoyance of Department Headquarters, some Inspectors removed the loop antennas and even refused to have the Department's name painted on the car doors.

No one would admit it, but cabinet ministers were fair game both in Ottawa and in their home constituencies. One Inspector was quietly very happy one year when he was able to get the Minister of Transport into court to pay a fine. The great depression years, when there was no unemployment insurance and only very limited welfare, added a new dimension to the Inspector's work. It was pretty tough when he came upon a home where there was obviously no income or support of any kind and the only pleasure the occupants got came from their radio. The Inspectors were pretty tight-lipped about how they dealt with those cases.

The names of those to be prosecuted in court, after approval by the Minister, would be sent through channels to the Radio Inspectors. Some might have as many as 500 cases. The Inspector would then have to do all the work needed to see each case through the court, filling in all the forms and appearing in each case to represent the Crown. The result was that each got to know the various judges in his territory and how each ran his court.

Inspectors became very knowledgeable in court procedures and very skilled in presenting the Crown's cases and enforcing the Radio Act and Regulations.

After the year's enforcement program wound up in the fall, the Inspectors got back to their work of inspecting all the other kinds of radio stations, locating and eliminating causes of interference and noise, conducting examinations and all those other jobs needed to keep order in Canadian radio communications. (The District Offices, as they were called in those days, did not assign frequencies or issue licences for transmitting stations.

Outside of broadcast receiving licences, Canada issued barely 10,000 radio licences and they were all prepared in Ottawa.)

Included in the Inspectors' tasks was monitoring. Then, Canada had only a few monitoring stations and they really only checked frequencies. Most Radio Inspectors were provided with a general coverage receiver. They were expected to set the receivers up in their homes and keep track of how licensees were using their stations.

The revenue from radio receiving licences was credited in an indirect way to the Canadian Radio Commission, later the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. In that sense, the UK practice was followed where receiving licence fees supported the BBC. It also justified the Department's program for the suppression of inductive interference to radio. When broadcast receiving licences were dropped, the CBC was given a larger annual grant by parliament. A special tax was also put on broadcast receivers at about that time on the basis that the money would be used for radio interference control. No clear relationship between tax receipts and interference control costs was ever established however, and when the tax was dropped in the early 70's, no action was taken to drop the control program.

|